The post What do the White Sox see in Curtis Mead? appeared first on Sox On 35th.

If you missed the news on Thursday, the White Sox traded Adrian Houser to the Rays at the last minute, receiving three players in return. One of these players was Curtis Mead, a former consensus top 100 prospect who has yet to see that pedigree translate to the major leagues.

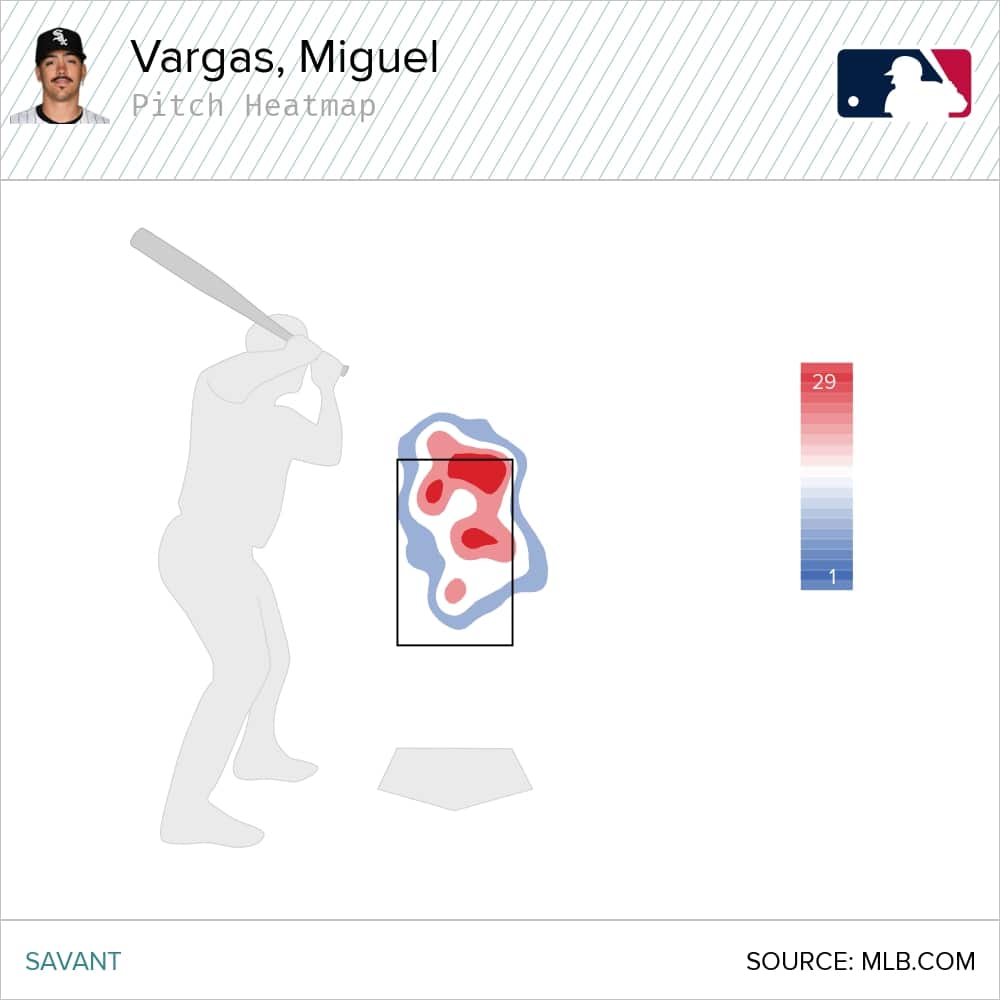

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the same description was used to describe the Miguel Vargas acquisition at last year’s trade deadline – something that Chris Getz was quick to point out as a successful outcome the last time they tried this.

This tweet caught my attention and served as the inspiration for this article. What have the White Sox identified that they can tap into? Are there things we can learn from their successful Miguel Vargas turnaround that can give fans more hope of something similar happening with Mead? What changes will have to be made?

Let’s dig into this and more below.

Setting the Foundation

You might be surprised by the following sentence for a player with a career 81 wRC+ and .238/.307/.322 slash line. But let’s start with some of the things that Mead does well, which give the White Sox a solid foundation to work with.

Let’s begin with his career 7.0% walk rate and 9.1% walk rate in 2025, both of which align well with a new-look White Sox offense that is in the top half of the league in walk rate. His ability to get on base is backed up by solid swing decisions, as his 23.5% chase rate puts him right alongside Chase Meidroth, Edgar Quero, Kyle Teel, and the aforementioned Vargas in that department. His zone-contact rate (Z-Swing%) for his career is 88.6% and 91.7% for 2025, both of which are by far the best on the team. His whiff rate overall of just 19.8% would rank in about the 75th percentile in the league, which makes his below-average strikeout rate of 25% a bit more peculiar until you realize that of his 33 strikeouts this season, 13 have been looking.

So, he makes good swing decisions, and when he swings (which might need to be more often), there’s a pretty good chance he will make contact. The contact he does make largely ends up in the air, as his 39.8% ground ball rate in 2025 is right in line with the rest of the White Sox offense, if not even perhaps a bit on the higher side of a team that collectively hits the third-fewest ground balls in the majors this season at just 38.7%.

Defensively, he’s been considered a man without a home due to his below-average arm, but his home might end up being second base, where he’s posted +2 Outs Above Average (OAA) in 40 chances in 2025. So, his defensive abilities seem to fit as well.

A friendly reminder that this is a small sample size that we’re dealing with here (just 132 PA in 2025), but there are encouraging trends. Now, let’s talk a little bit about what needs to be worked on – and we will start with a little bit of a comparison to Vargas.

Handling the Heat

If you want to be able to play for the White Sox, you have to be able to hit a fastball. Since July 1, the team has ranked fourth in all of baseball in slugging percentage on fastballs and eighth in wOBA. Those numbers jump to second and third, respectively, since the All-Star Break.

How does Mead do here? Well, he struggles with velocity, particularly on pitches at or above 95 mph. Here’s how he’s hit against the fastball in his major league career:

| AVG | SLG | OPS | ISO | wOBA | xwOBA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastballs <= 94 mph |

.292 | .417 | .794 | .125 | .351 | .359 |

| Fastballs >= 95 mph |

.200 | .200 | .498 | .000 | .241 | .264 |

That 95 mph threshold is an important one for a couple of reasons. The first reason is that it’s an area where the White Sox have seen some of their largest improvement offensively against the fastball. The second reason is that Mead’s numbers against fastballs – and in particular, the fall off at the 95 mph mark – look similar to another White Sox player: Miguel Vargas. Before 2025, the former Dodger put up these numbers:

| AVG | SLG | OPS | ISO | wOBA | xwOBA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastballs <= 94 mph |

.177 | .383 | .681 | .206 | .301 | .328 |

| Fastballs >= 95 mph |

.130 | .180 | .428 | .050 | .209 | .225 |

It wasn’t smooth sailing for Vargas, even at velocities below 95 mph, but there was a clear drop-off that made it hard to accept the idea that more at-bats would be the magic solution.

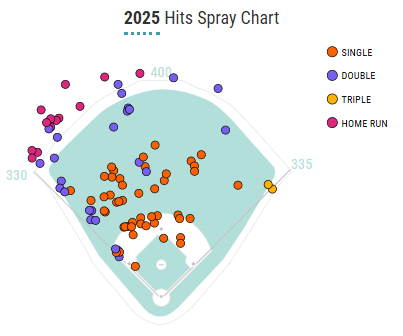

You know the story from there, however: Vargas and the White Sox undertook a swing change, and the results since April 23rd of this season speak for themselves:

| AVG | SLG | OPS | ISO | wOBA | xwOBA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastballs >= 95 mph |

.215 | .400 | .720 | .185 | .320 | .408 |

Noticably improved, with advanced metrics that would appear to suggest room for further improvement. This is where the original tweet that inspired this post, as well as certainly a large number of other White Sox fans’ posts, start to get the idea of, “Well, they did it with Vargas, they can do it with Mead too.”

But saying, “He needs to hit more fastballs,” is an incomplete answer. How did the White Sox do that with Vargas, and how might they be thinking of doing it with Mead?

Fun with Swing Paths

*WARNING*: The rest of this article has a heavy focus on the analytics behind the swing. You’ve been warned.

It’s really at this point that the comparisons between Vargas and Mead should stop. They both have a similar problem, but there are going to be two vastly different ways of approaching this problem. Let me explain.

Let’s start with Vargas briefly. Those “20 pounds of muscle” articles from Spring Training weren’t wrong: Vargas got stronger over the offseason, evidenced by a slight increase in average bat speed (+0.8 mph) and a three percentage point increase in Fast Swing Rate – percentage of swings at or above 75 mph – from 8.3% in 2024 to 11.6% in 2025. Vargas already had a strong foundation in his swing path, as he ranked 37th among all hitters (minimum 200 swings) with 62.3% of his swings registering in the “Ideal Attack Angle” range of 5-20 degrees. This has improved to fifth among qualified hitters in 2025.

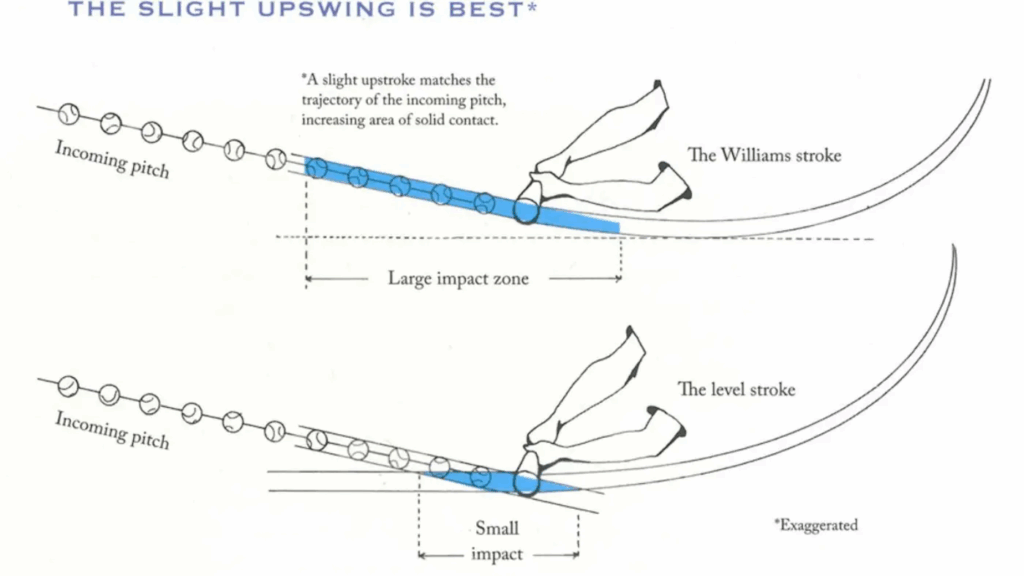

(Small aside: For those newer to this terminology, the “attack angle” of a swing refers to the direction the barrel of the bat is traveling, relative to the ground, as it impacts the ball. Positive attack angles mean the barrel is traveling upward at contact. 5-20 degrees is considered the “ideal attack angle” because attack angles in this range produce more line drives and fly balls, leading to more extra-base hits and a higher slugging percentage as a result.)

For the White Sox and Vargas, the fix was simple: find a way to maximize some already strong trends in his swing path by fixing Vargas’ weakness to fastballs, particularly ones up in the zone.

You know the rest of the story from there: his hands were raised sometime around April 23rd of this year, and the results speak for themselves – so much so that they give the White Sox confidence they can do the same with Mead.

Now, let’s get to Mead. Theoretically, the Aussie should have a leg up on Vargas in terms of strength. His average bat speed is 73.2 mph – similar to Wyatt Langford, Brandon Lowe, Juan Soto, and Salvador Perez, while being nearly three miles per hour faster than Vargas – and he registers “fast swings” 36.5% of the time, ranking in the top 60 in the league in both categories.

Yet, Vargas squares up the ball more often than Mead.

| Squared-Up as a % of Contact |

Squared-Up as a % of all Swings |

Bat Speed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miguel Vargas | 35% | 29.2% | 70.6 mph |

| Curtis Mead | 30% | 25.1% | 73.2 mph |

(“Squared Up” in this context refers to, per Baseball Savant, how much exit velocity you got as a share of how much exit velocity was possible based on your swing speed and the speed of the pitch. A swing that is 60% squared up, for example, tells you that the batter attained 60% of the maximum possible exit velocity available to him, based on the speed of the swing and pitch. For Statcast purposes, any swing that is at least 80% squared up is considered to have been “a squared-up swing.”)

To clarify, this reads: “Miguel Vargas squares up the ball 35% of the time he makes contact with it and 29% of the time he swings the bat.” In simpler terms, what this shows is that, while Vargas may not be able to swing as hard as Mead, he’s been able to be more efficient with the power he does supply.

So, what’s the difference, you ask? It’s the answer to this whole article: their swing paths.

Fixing Curtis Mead

Cool, “swing paths.” So, we’re done, right? Not yet. Let’s dive a bit further into attack angles and swing directions to understand what needs to change.

We defined attack angles above, and “swing direction” refers to the angle, relative to the center of home plate, that the barrel of the bat is pointed at contact (measured in degrees to the pull side or opposite side).

For ease, we will continue the imperfect comparison between Vargas and Mead for a bit longer.

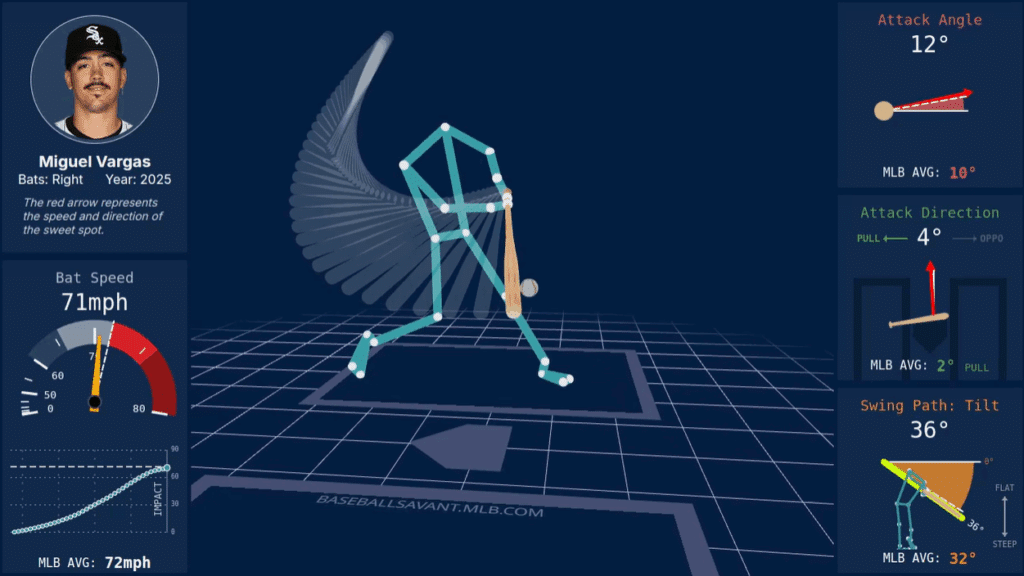

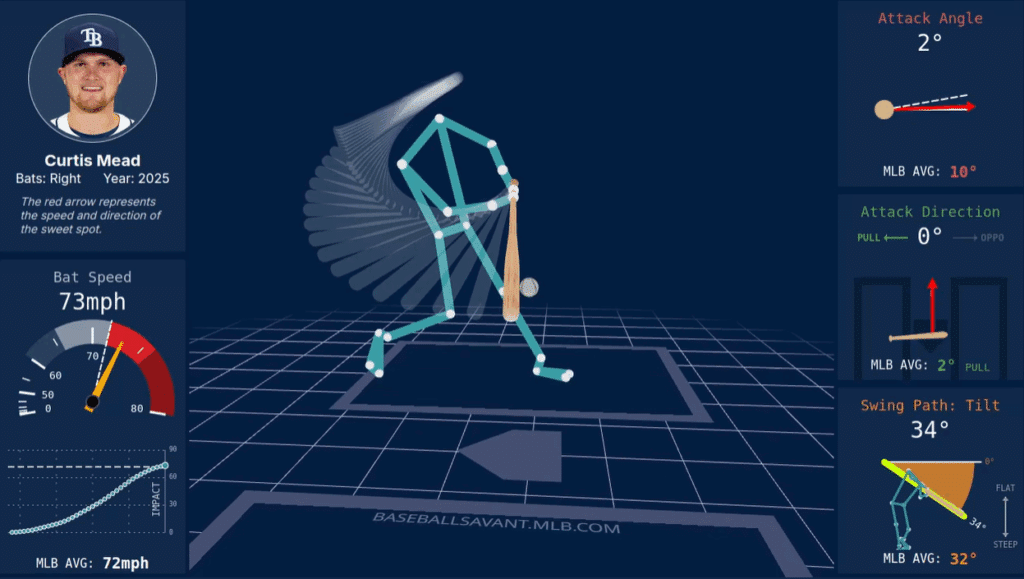

| Attack Angle | Attack Direction | Ideal Attack Angle % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miguel Vargas | 12 Degrees | 4 Degrees (Pull) | 67.2% |

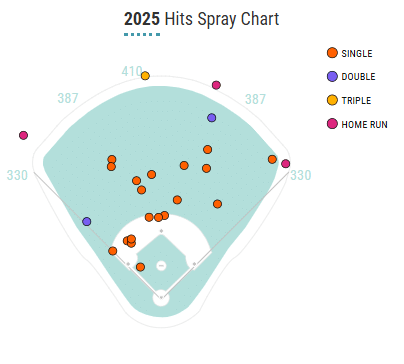

| Curtis Mead | 2 Degrees | 1 Degree (Oppo) | 34.5% |

So, now we get to the other burning question: “Why should we not be comparing Mead to Vargas?” The answer: while Vargas’ hands and swing path led to issues up in the zone, Mead’s flatter approach – as evidenced by his lower attack angle – leaves him vulnerable in the bottom of the zone. You can’t do much damage if you’re chopping the ball into the ground or popping up anything down in the zone, especially when you have 15-25 homer potential.

As for pitches up in the zone, Mead has handled them and seen varying levels of success. But at the same time, a lower percentage of ideal attack angle outcomes works against him, leading to a lower percentage of opportunities to create real offensive damage in the long run (based on expected statistics).

BA/xBA, 2025

” data-medium-file=”https://www.soxon35th.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-01-073017-300×166.png” data-large-file=”https://www.soxon35th.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-01-073017.png” data-id=”73135″ src=”https://www.soxon35th.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-01-073017.png” alt=”” class=”wp-image-73135″ />

wOBA/xwOBA, 2025

” data-medium-file=”https://www.soxon35th.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-01-073041-300×170.png” data-large-file=”https://www.soxon35th.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-01-073041.png” data-id=”73134″ src=”https://www.soxon35th.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-01-073041.png” alt=”” class=”wp-image-73134″ />

How do we know this attack angle stuff even matters? Well, plenty of research has been done on this concept by places such as Driveline, and being on plane with a pitch, or having an attack angle that matches the incoming pitch angle, has multiple benefits:

- Distance in the Zone: A wider margin of error allows the hitter to make more consistent contact with the ball.

- Better Transfer of Energy from Bat to Ball: When the bat strikes the ball, any offset in the attack angle and incoming pitch angle results in potential energy lost.

And, if you don’t trust me and Driveline, I’m sure you’ll trust Ted Williams and his 1971 book The Science of Hitting, from which the following graphic comes, won’t you?

Now, we’re a bit closer to our answer: the White Sox likely see an opportunity to make a slight change to increase Mead’s attack angle to tap into his power. What this will include is easier said than done – and that’s coming from someone who’s only done it at the high school level as a coach. There is an endless number of drills that are utilized to teach improvements to attack angles, and while I wouldn’t recommend trying to copy Aaron Judge, tee work, flips, and feedback balls have gone a long way for a lot of hitters.

As for how much to increase his attack angle: that’s another question the White Sox will need to personalize to Mead. It doesn’t need to be steep, but somewhere in the 8-12 degree range feels right to me, just based on the data. Based on Mead’s strength and mechanics, this number can certainly fluctuate a little.

But changing the attack angle through mechanics alone isn’t the solution. To expand further, Mead needs to be able to pull the ball in the air more, as we know that leads to the highest likelihood of maximum damage as a power hitter. He currently holds a 12.5 PullAir%, which means he pulls in the air just 12.5% of the balls he hits. Said differently, he’s a player with 15-25 homer potential who’s been pulling the ball in the air as often as Meidroth. If you want to keep the imperfect Vargas comparison going one last time, he’s up at a 25.0 PullAir% this season, so Mead does have some work to do if he wants to tap into his power potential.

Much of that has to do with where Mead is contacting the ball in the zone. Statcast now has this awesome swing path visualization tool. To show it off, here are Vargas’ and Mead’s 2025 swing paths side by side.

In those images, you can see Mead’s shorter, more compact swing that leads to a flatter bat path at contact and a smaller margin for error. But, you can also see that he impacts the ball (called the “intercept point”) way farther back on the plate than most, nearly 5.5 inches behind the front of the plate, 20th-furthest back in the league. Wrapping his barrel as much as he does (the top of the bat is pointed towards the pitcher) certainly doesn’t help this either, as it takes longer for the barrel to travel through the zone.

Now, it isn’t exactly a death sentence to hit the ball this far back in the zone, but if you want to do it as a power hitter, your name better be Mike Trout or George Springer (though they have attack angles of 8 and 13 degrees, respectively). Everyone else has to do it like normal people and contact the ball further out in front of the plate.

Attack angle and attack direction are both tied to where you’re contacting the ball in the zone as well – your swing is naturally on a more “upper cut” path later in the sequence. So, the White Sox could theoretically try to bypass any major in-season swing changes and ask Mead to simply focus on hitting the ball further out in front of the plate. Based on his chase rates and bat speed, he does have the pitch recognition and strength to sacrifice some reaction time to naturally increase his attack angle by a few degrees simply by hitting the pitch out in front further. Perhaps the White Sox try this and realize he doesn’t need to make as many major changes as it might appear on the surface. Like I said, the science of hitting is insanely tough, and while we have a lot of data, we don’t have all of it as fans.

To Mead’s credit, all of this is something he and the Rays had begun trying to fix. He made a mechanical adjustment in early May, and during his next 77 plate appearances, he hit .269/.364/.448, good for a .357 wOBA. Here’s the problem: on pitches down in the zone, he still hit just .158 with a .368 SLG and .244 wOBA. On fastballs over 95 mph? .267 AVG, .267 SLG, .290 wOBA. No real changes to his attack angle and attack direction occurred, so no real changes to the areas that plagued him the most took place.

Based on the video below, however, these changes should actually make it easier for the White Sox to begin implementing some of their own changes, as his more simplified stance eliminated some of the many moving parts to his swing and should allow him to “be on time” more often with an improved swing path and philosophy of “hitting fastballs out in front.” This strategy isn’t without its risks, however, with an increase in swings and misses being the obvious one. Theoretically, the increased offensive output should be worth any increase in swing and miss that occurs.

One smaller thing has stuck out to me as well when looking at his recent videos, and that his landing foot tends to step out a bit at times, pulling his front hip along with him and leaving him vulnerable to pitches on the outer part of the zone. This is confirmed by some of the zone breakdowns above, as he has some of the lowest expected statistics in the outer third of the zone. However, this is a rather simple fix with repetition, and nothing will be more important than starting to improve (1) the attack angle, and (2) the intercept point of Mead’s swing. If they can do this, some of those issues with fastballs will also begin to fix themselves, especially with the team’s clear philosophy of hunting fastballs.

Now, remember, there are no guarantees that anything listed in here works. As mentioned before, Vargas and Mead were working with very different issues, and while Mead may have the strength that Vargas lacks, Vargas’ swing needed simpler changes to make a big difference. As we’ve seen with Mead, the changes he made helped, but they didn’t solve his ultimate problems, because his problems are a little bit bigger than Vargas’.

This also isn’t a one-size-fits-all strategy that can be used on any player struggling to tap into his power potential. Things like changing attack angles, hitting the ball in front of the plate, and pulling fly balls aren’t for everyone – I wouldn’t write the same article about Chase Meidroth, for example, because he and Curtis Mead aren’t the same ballplayer. The White Sox will have to be incredibly methodical about the drills they use in helping make changes to Mead’s swing, and treating his case the same as Vargas’ will not lead to the same outcome. Teaching someone to hit a baseball, in today’s game, is probably one of the hardest things to do, and Ryan Fuller and Marcus Thames have their work cut out for them.

At the same time, while I’ve unintentionally discounted some of the changes Mead already made, the fact that he posted an .811 OPS for any period proves that the White Sox are correct in their assessment that there is talent available to work with. His history of power in the minors also proves that there is power potential to be unlocked – in other words, the White Sox shouldn’t be trying to turn him into Chase Meidroth. If you watch enough video, you’ll find that Curtis Mead has already made plenty of adjustments throughout his career. While none of them have been the big change needed, he’s clearly coachable, so it’s at least worth the White Sox trying – even if you’re someone who believes the Rays “gave up” on Mead.

Remember, Mead was acquired for someone who made just 11 starts for the White Sox. At 32 years old, and at the peak of his performance, it was smart for the White Sox to trade Houser as a rental. There’s a pretty decent chance of some regression in Houser’s performance – but we can’t discount what he did here, as he brought the White Sox two pitchers with solid potential and one position player with power upside, which the White Sox lack badly in the system.

Perhaps lightning strikes twice for the White Sox, and they’re able to make the changes necessary for Mead to be a middle-of-the-order impact bat over the next five seasons. If not, his floor of a superutilityman isn’t completely useless, especially since the current options for that role – Lenyn Sosa and Brooks Baldwin – are out of options and struggling mightily, respectively.

At the end of the day, with the changes made to Miguel Vargas and Colson Montgomery serving as proofs of concept, Ryan Fuller and Marcus Thames have at least earned another opportunity to work on a project with MLB experience.

And for once, it’s nice to have even a sliver of hope that this sort of project is one they might be able to turn around.

Follow us @SoxOn35th for more throughout the season!

Featured Image: Wendell Cruz-Imagn Images

The post What do the White Sox see in Curtis Mead? appeared first on Sox On 35th.