MACOMB, Ill. — Swinging their pompoms in sync, the Westernettes danced in the sun on a recent Friday morning as the Marching Leathernecks played their traditional tune “Let’s Go ‘Necks!” in the shade.

Three days before classes were to start, the dance team and marching band performed before a large crowd outside the College of Fine Arts and Communication Recital Hall on Western Illinois University’s main campus. This was a celebration of sorts, warranting an appearance by Ray, the school’s beloved English bulldog mascot clad in a WIU sweater of purple and gold.

Inside the recital hall, the school’s president, Kristi Mindrup, took the stage with other university administrators and mentioned the school’s enrollment figure in 1973 of 15,469 — three times the roughly 5,100 estimated enrolled this school year. But she urged attendees not to dwell on the past, quoting former President Theodore Roosevelt: “Comparison is the thief of joy.”

“WIU will be successful at any size because of our people and our dedication to our mission,” Mindrup said during the Aug. 22 event. “There is one question: Are we ready to let go of what we were and to lift up where we are now in order to evolve into what we will be?”

With enrollment dropping drastically over the last two decades, WIU is in the same company as many Illinois public regional universities. Sometimes called directional universities, the schools representing geographical areas of the state, including Eastern Illinois University, Northern Illinois University and Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, are facing some of their most significant challenges in modern times in attracting students.

The enrollment drop is part of a national trend as public schools are relying more on tuition and fees to balance their books than on government assistance. In Illinois, the struggle has been especially pronounced. The state has faced an array of budgetary challenges in recent years brought on by growing pension debt, a budget impasse that has affected higher education and decimated state services, and national economic downturns from the Great Recession to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Institutions of higher education are under fire these days by critics who say they serve elites, but that is not who regional schools typically attract. Regional schools have historically been a draw for students from working-class families, often students of color, students from rural areas, and those who may not otherwise go to college. But increasingly in recent years, the schools have had to compete against bigger name, out-of-state universities looking to attract Illinois high school graduates.

WIU had more than 13,500 enrolled students in fall 2004, but at the beginning of last school year enrollment hovered around 6,300, according to Illinois Board of Higher Education figures. At SIU in Carbondale, enrollment dropped by about 45% in the last two decades, from roughly 21,600 to around 11,800 in fall 2024, the data show. For EIU in Charleston, fall 2004 enrollment stood around 11,650 before dropping to a little more than 8,500 last year.

Northern Illinois in DeKalb had about 24,800 students in fall 2004 but lost more than 9,000 by last year. On Chicago’s Far South Side, Chicago State University’s enrollment declined from more than 6,800 to 2,200 over the past 20 years, while enrollment at Northeastern Illinois University on the city’s Northwest Side dipped from more than 12,100 20 years ago to 5,700 last year, the figures show.

Equitable funding has backing

While observers say chronic underfunding is largely to blame for the steep enrollment drops at regional universities, the University of Illinois system, which is significantly more well-known nationwide as the state’s flagship college system, has not had a problem with enrollment.

Each of the system’s three schools — in Urbana-Champaign, Chicago, and Springfield — has increased enrollment over the same 20-year period, with figures at the main campus in Urbana-Champaign climbing from 40,500 in fall 2004 to 59,000 last year.

Another Illinois university, Illinois State University in Normal, saw record enrollment this year with nearly 22,000 students. In fall 2004, enrollment was less than 21,000.

The problems facing the regional universities appear largely to be systemwide, causing the Democratic-controlled General Assembly to introduce a proposal that would institute an equitable funding model for Illinois’ public universities. It’s a similar concept to what the legislature passed in 2017 to benefit kindergarten-through-12th-grade school districts in low-income communities by identifying gaps in funding to help guide decision makers to allocate funding more fairly to the institutions.

The legislation would prioritize the most under-resourced universities that are now relying more on tuition dollars. So far, the proposal hasn’t advanced through the legislature despite having 29 House Democratic sponsors, including House Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch of Hillside.

“It’s an issue that’s very important. You know, but talking to the governor, talking to the Senate president, one of the things we know is funding’s an issue right now,” Welch said in late August. “I don’t want to pass an empty law. I want to make sure that when we do get it across the finish line, that we’re able to fund it and get the money to universities that need it.”

The proposal, according to experts, would call for $135 million annually to be divided among the regional schools and other public universities based on need. But a funding mechanism still needs to be worked out amid the state’s ever-complex budget situation that includes greater funding requests for Chicago Public Schools and Chicago-area transit.

Gov. JB Pritzker’s administration has touted how it has increased funding for Illinois’ universities since he became governor in 2019, pointing to the more than $770 million the state has set aside annually in grant funding through the AIM HIGH and Monetary Award Program, or MAP, initiatives that help 162,700 students. While Pritzker said he supports an equitable funding model concept for the regional universities, there’s “a lot of complication to it,” he said.

‘We need to invest’

“It isn’t as simple as just ‘well, let’s do it like K-12 does it.’ That isn’t how it works for universities,” Pritzker said recently. “But it’s certain that we need to invest in particularly the colleges, the universities that have been left out and left behind, the ones that have been disinvested from.”

State Rep. La Shawn Ford, a Democrat from Chicago’s West Side who heads the Illinois House Higher Education Appropriations Committee, said if the Pritzker administration made the funding formula proposal a priority, there’d be less of an obstacle to getting it passed.

“If we look at those two scholarship programs and have meetings with the universities and say, ‘Look, how could we make college more affordable? Should we put more money into your universities directly? Should we reduce the direct funding of AIM HIGH and MAP and you could lower your tuition costs … and eliminate some of these fees?’” Ford said. “I think that has to be the strategy.”

In 2024, a group created by the General Assembly to recommend how to implement a higher education-focused equitable funding formula described a framework in a report that included determining a “unique funding level” for each institution based on its students’ needs. The Illinois Commission on Equitable Public University Funding encouraged better access to educational resources for lower-income students and helping the schools rely less on tuition dollars.

According to the funding model measure, so-called adequacy targets would be established for each school — financial needs to cover teaching expenses and student services, the school’s research and public service mission, operations and maintenance and “to support closing gaps in enrollment, retention, or completion for underserved students.”

Recent “adequacy target” data show Western Illinois ranked last in Illinois among 12 public universities, with 45.7% of its target being fully funded, meaning WIU only has resources to cover about $88 million of the roughly $192.2 million it needs.

The second lowest-ranking school was Northeastern Illinois at 46.6%, the modeling shows, followed by Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville at 46.8% and Eastern Illinois at 48.3%.

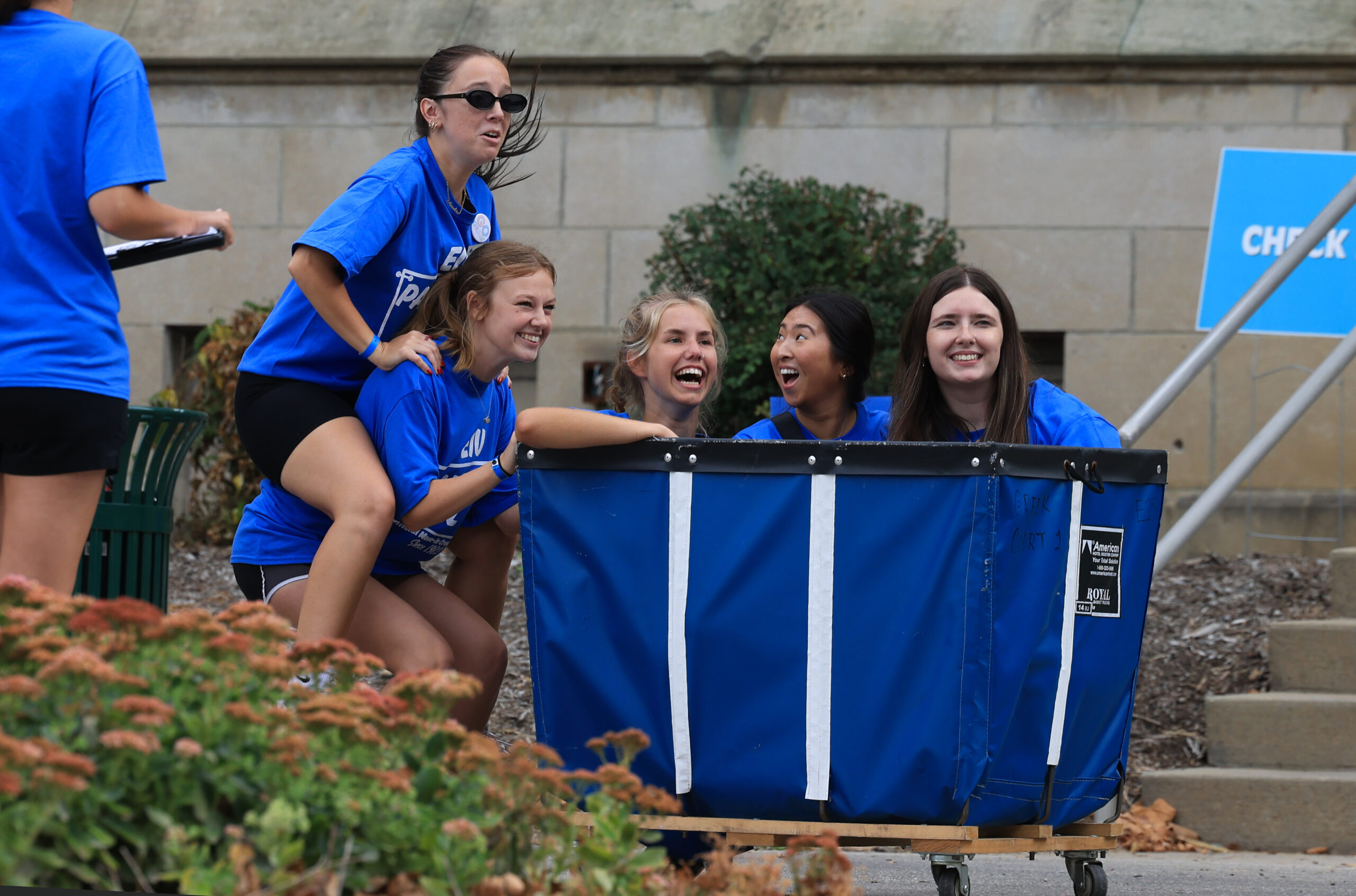

“If we’ve got more funding, we’re going to do more marketing. We’re going to be attracting more students,” Josh Norman, EIU’s vice president for enrollment management, said as he greeted students outside the school’s Lawson Hall dorm on moving day last month.

Norman said campus visits are key to getting students to want to come to the school, which is about 170 miles south of Chicago. But he admits it’s gotten more difficult because of competition from out-of-state schools.

“Sometimes we’re hiring a bus, and we’re busing them down from CPS (the Chicago Public Schools) or from the suburbs,” he said. “Sometimes we’re buying train tickets. You know, it’s like we’ve got to make it accessible in order for these students and parents to make the time to make Eastern a priority.”

U. of I. has concerns

Perhaps not surprisingly, the school with the highest adequacy target funding rate was the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign at over 88%, according to the modeling.

U. of I. opposes the equitable funding legislation, with the university saying it would limit its ability to offer financial aid, could potentially drive up tuition costs and fees and might reduce the school’s capacity for research.

While the school supports “several of the key aspirational goals of the bill,” a spokeswoman in an email said U. of I. hopes to discuss a solution that includes considering “retention, graduation, and performance metrics, strengthening its connection to student success.”

According to the 2024 commission report, citing an analysis from a tax and budget watchdog, the state’s investment in colleges and universities dropped by 46% in inflation-adjusted terms from 2000 to 2020.

As that happened, many schools became increasingly dependent on tuition and fees, prompting them to raise costs for students. According to the commission, for instance, average tuition and fees at public universities in Illinois increased 63% in inflation-adjusted dollars between the 2004-05 and 2016-17 school years.

At the same time, a sizable percentage of Illinois high school graduates have chosen to go to college out of state. The rate of high school graduates leaving Illinois to attend college was 47.6% in 2021, significantly higher than 29.3% in 2002, according to the state Board of Higher Education figures.

Robin Steans, president of Advance Illinois, a bipartisan education policy and advocacy organization, noted investments in Illinois higher education have improved in recent years, but she said there’s still so much ground to make up. She also noted a shift in who attends college and when, emphasizing universities must adapt to this change.

“We should be thinking more creatively about who we should be, who we’re trying to get back into higher ed because there are people who, maybe they didn’t go straight out of high school, but they’re ready to go now,” Steans said. “They understand the value of it now, and so I think universities have to be more adaptable about how they are doing that recruitment.”

WIU, which also has a campus in the Quad Cities, announced a number of layoffs, including 89 people — 57 of them faculty members — in August 2024. A hiring suspension and spending freeze were also implemented; more than 100 vacant positions were eliminated from future budgets, various contracts were discontinued and departments were consolidated.

“Since the state budget impasse (between 2015 and 2017), the university finances have been a challenging topic, shaped further by decades of enrollment pressures, staffing impacts, financial strain and increasing deferred maintenance needs,” Ketra Roselieb, WIU’s vice president for finance and administration, said at the Aug. 22 event. “I often dream of prior fiscal environments when we would hurry up and spend funds before (the end of a fiscal year) or, honestly, when a 25% reduction in operating expenditures was all we had to worry about.”

Not all bad news

But there are some bright spots at WIU, university officials said, including a high rating it received from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, a renowned higher education think tank. The ranking was based on the school’s quality of education and graduates’ success in the job market. The school is also constructing a new performing arts center with as much as $36.35 million devoted to the project in the current state budget.

The drop in enrollment is also palpable outside campus to people in Macomb, a town that saw its population drop from more than 19,000 in 2010 to about 15,000 a decade later.

In Macomb’s quaint courthouse square, where a stainless steel sculpture of a pair of giant spinning dice pays homage to a Macomb resident who invented the board game that inspired Monopoly, Mefail Kadriu said he noticed fewer people in town even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Just the foot traffic around Macomb, especially around the square, unless there’s a big event going on, there’s not much going on,” the 20-year-old said from his family’s restaurant, Mili’s King Gyros. He said he grew up in Macomb and is attending WIU this year to study marketing. “Just even driving around town when I’m not at work, like, you can just tell the town is not as much as it was even 10 years ago.”

But Steven Brody, executive director for the Macomb Area Chamber of Commerce, thinks the town is on the rise. He cited the recent openings of a Chipotle, Hobby Lobby and T.J. Maxx in Macomb, which he called “huge wins” because sometimes businesses, he said, have population requirements.

Brody also said there’s been a tourism influx because of “Macombopoly,” a play on Monopoly that opened about a year ago and has gamers using an app while circling the courthouse square. He also mentioned that the chamber and city officials have discussed constructing a sports facility for basketball and volleyball, with seating for 4,000, which Brody believes could be a “game changer.”

Like Macomb, Charleston, home to Eastern Illinois, has lost population; In 2010, it had close to 22,000 residents. Ten years later, the population had dropped to a little over 17,000.

Colleen Peterlich, president and CEO of the Charleston Area Chamber of Commerce, said she thinks the gradual enrollment decline at EIU and the drop in the city’s population probably go hand in hand. But she emphasized how critical it is for the community to figure out how to retain young professionals and identify what businesses to attract.

“There’s always room for improvement with everything. There’s always growth with everything. But we’ve got to get people here. And we do have some good space. We have good railroads,” said Peterlich, a Chicago-area native who also said she has lived in Charleston for decades after attending EIU. “But you’ve got to get the word out. You’ve got to talk about where you live.”

‘Feels more like home’

Despite enrollment woes at EIU and WIU, the students who made those schools their number one choice say they did it for good reason.

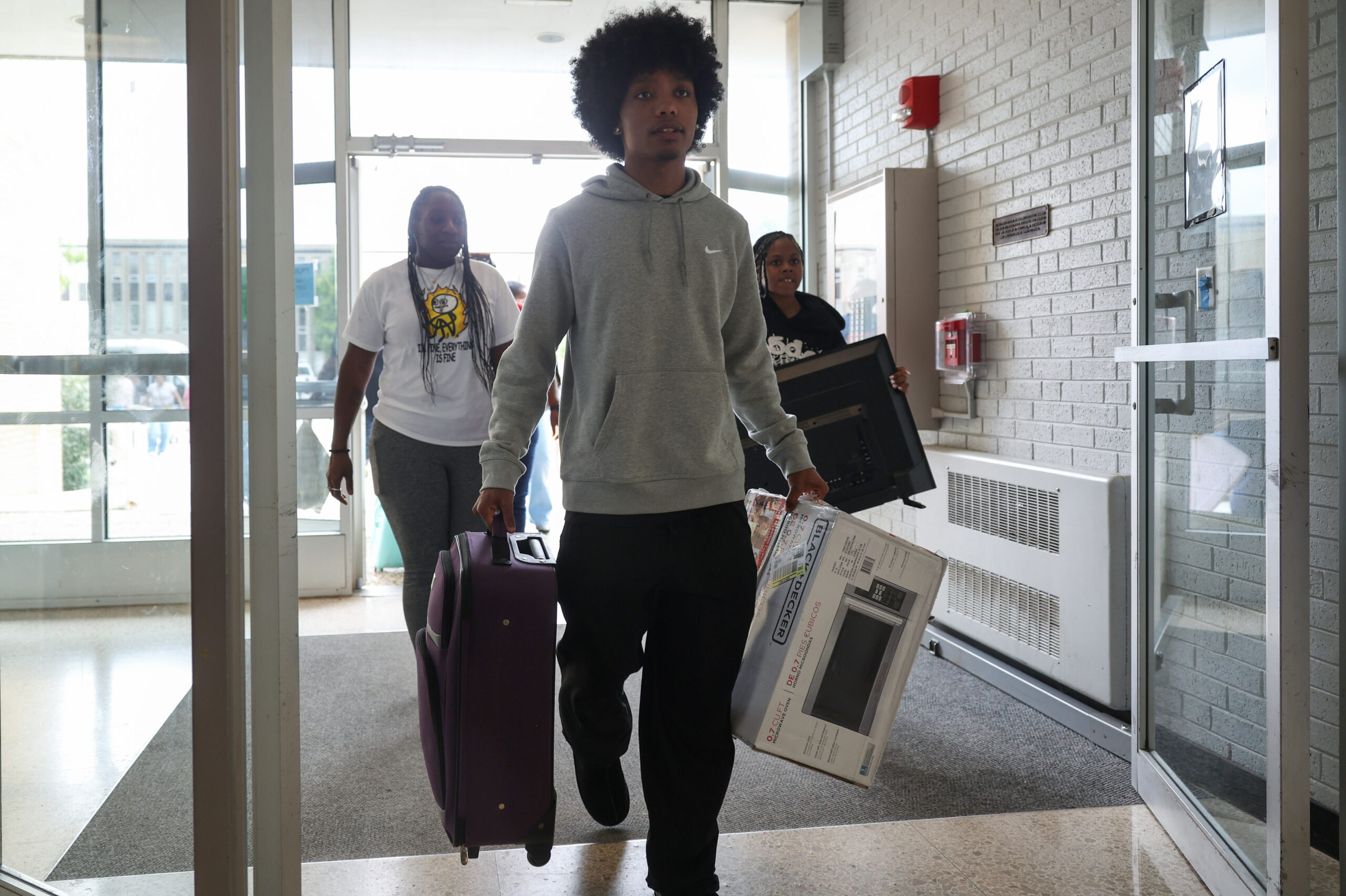

At EIU’s Lawson Hall, a freshman from the nearby town of Newman, Lela Duzan, 18, said she chose the university because she wants to become a high school history teacher and her mother attended school there.

“It’s becoming a real problem if they can’t get people to educate your kids,” said Lela’s father, Chris, who was helping his daughter get settled into her dorm. “Teachers are a very underrated profession, I would say. Very underpaid, really. It’s hard to get people that want to become teachers anymore.”

Adrianna Haskins said she came to EIU because it was affordable and she felt at home on campus.

“I’m from a small town. So, this feels more like home,” said Haskins, of Warsaw, 215 miles west of the college. She said she might double major in English and acting. “I’ve been here a few times just as a guest. And I’ve met a few people, and it’s been super great.”

Back at Western Illinois, Jayden Washington’s interests include photography, filmmaking and sports.

Inspired by TV football analysts such as Pat McAfee of ESPN’s College GameDay, the 18-year-old traveled 211 miles from Chicago’s south suburbs to study broadcasting and journalism at WIU. As an added bonus, he discovered the great view of the sunset over the sprawling Macomb campus with his camera when he got settled into dorm life on the ninth floor of Thompson Hall, a glossy, modern-looking high-rise complex that can house about 1,000 students, and is currently about 66% full.

As other students were moving in, Washington stood outside the imposing dorm tower with family members. He sounded upbeat and said he imagined the possibilities of his new life as a college student.

“There’s a podcast I want to do. A couple of my dorm mates want to do a podcast,” he said. “The campus is pretty. There’s some really nice photo spots. Like, I can walk around with my camera and take a bunch of pictures, especially during the fall when the leaves start changing. That’s what my R.A. (residential adviser) told me.”