The post Grant Taylor is the White Sox High-Leverage Arm: Is that a Good Thing? appeared first on Sox On 35th.

The first time I heard that Grant Taylor would pitch for the White Sox in 2025 was on an early-season podcast episode. Although I didn’t buy it initially, the discussion about a promotion being imminent and largely predetermined stuck with me. About a month later, though, a campaign of breadcrumb dropping continued.

First, some media members coyly hinted at Taylor being the next man up after the promotion of Kyle Teel. Then, Connor McKnight ramped up the Taylor talk on the CHSN broadcast. For those who had eyes with which to see, that June 9th call-up announcement didn’t come as a total surprise.

Truthfully, nobody should’ve been surprised. Big league stuff has never been a question for Taylor. The unrealized Robin to Paul Skene’s Batman at LSU (or maybe the other way around), the 6-foot-3 righty has yet to face a great deal of adversity on the mound at the professional level.

Drafted during his recovery from Tommy John Surgery in 2023, the following season brought a 2.33 ERA and 44.0 K% across two minor league levels. The obvious drama surrounding him this season was his swift move from a strictly innings-limited starter to a high-leverage reliever while at Double-A in Birmingham. I feel as if Sox fans have spent too much time talking about this switch, and the casualty of this discursive imbalance is that analysis of his actual on-field performance at the big league level has fallen by the wayside.

So that’s what I intend to do in this piece; I want to analyze Taylor’s early performance to understand his current, frankly, uneven results. Thinking about relievers analytically is difficult because, even compared to rookie starters, we have so little statistical track record to pull from.

As of August 7th, Taylor has pitched 22 innings at the big league level in 2025. This is far too small a sample size for numbers like ERA, BABIP allowed, or HR/FB to normalize – margins of separation between relievers in catch-all stats like fWAR are so slim as to be meaningless. So, how do we understand what’s signal and what’s noise within his 4.09 ERA and 32.2 K% and the underlying data that undergird those figures?

No Ice in His Veins?

Part of what makes gauging Taylor’s performance so difficult, besides the small sample, is the question of what the White Sox want the right-hander to be this season.

Thus far in 2025, Taylor has opened, entered the game in the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth innings without regard for the handedness of the batters he’s to face, and pitched in a multi-inning relief role. Despite the wide range of hats he’s been made to wear, there are only a few game conditions that Venable seems comfortable dropping him into. Besides his two stints as an opener, Taylor has only twice entered a game in which the White Sox were trailing (in both instances the Sox were down one run), only once entered a game that was mostly out of hand, and only twice entered the game in the middle of an inning. The Sox are using Taylor as a queen-on-the-chessboard leverage piece.

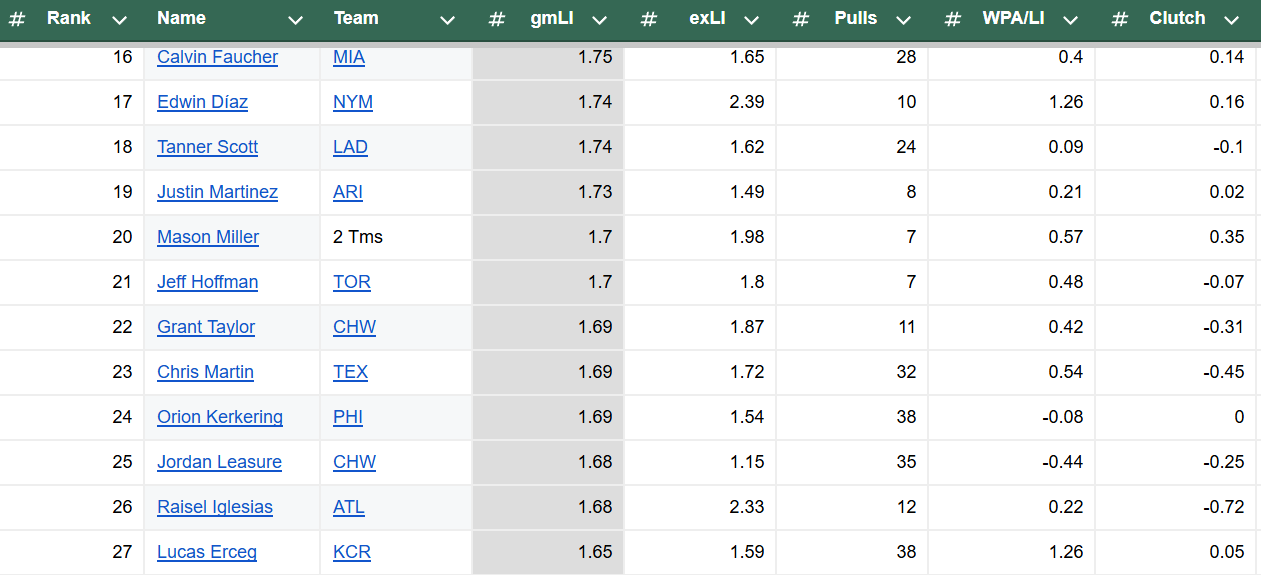

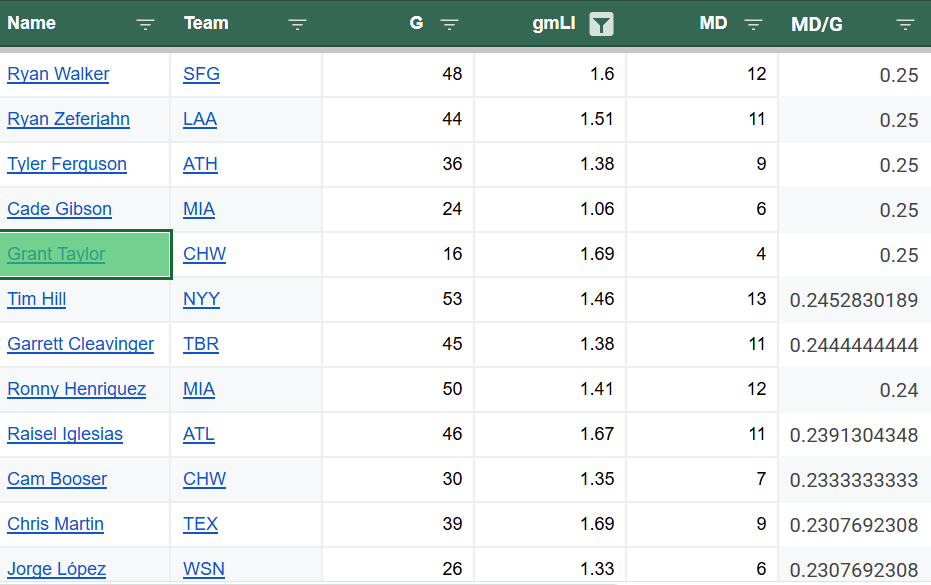

This role is further understood by empirical examination by looking at the average Leverage Index when Taylor enters the game, or his gmLI. Leverage index is, in essence, a statistical estimation of how important a single moment in a game is in determining the game’s win-loss result (higher = more critical). Currently, Taylor enters the game with an average leverage index of 1.6, good for 33rd among 545 relievers with at least 10 innings in 2025. If you remove his two stints as an opener, however, Taylor jumps to a gmLI of 1.69 (good for 21st in that same cohort), putting him in the range of Mason Miller and Cade Smith.

Regardless of the exact gmLI figure you choose, the White Sox have demonstrated that Taylor is their guy when they need three outs. But what if I told you that, despite the emphatic punchouts and Pitching Ninja spotlights, he’s not been particularly good at it so far?

FanGraphs has stats called shutdowns and meltdowns that mark when, in the course of a pitcher’s appearance, his team’s probability of winning a game increases or decreases, respectively, by 6% or greater. Only looking at games in which Taylor entered in relief, he has the 53rd highest rate of meltdown among those 347 pitchers with at least 10 innings of relief this year. If you were to pare that group down by only looking at players that enter with an average gmLI of 1.06 (this appeared to weed out starters piggybacking an opener and the worst-of-the-worst relievers), Taylor rises to the 29th highest rate of meltdown in the league – around 25%.

What’s causing this dissonance between highlight reel pop and on-field struggles?

Does Grant Taylor have the Good Stuff?

Now there’s a very easy way to write his meltdowns as small sample death-by-BABIP incidents. Certainly, his low-4’s ERA is belied by his 2.34 xERA, 1.70 FIP, and the fact that he’s yet to give up a home run. And it’s not like he’s chucking an odd meatball that gets punished in these blowup outings. Taylor is fifth among relievers with at least 10 IP in FanGraph’s Location+, his 4.2 barrel% allowed is well better than league average, and, among pitchers with at least 25 batted ball events, Taylor gives up the sixth-lowest rate of pulled fly balls. So what’s the problem?

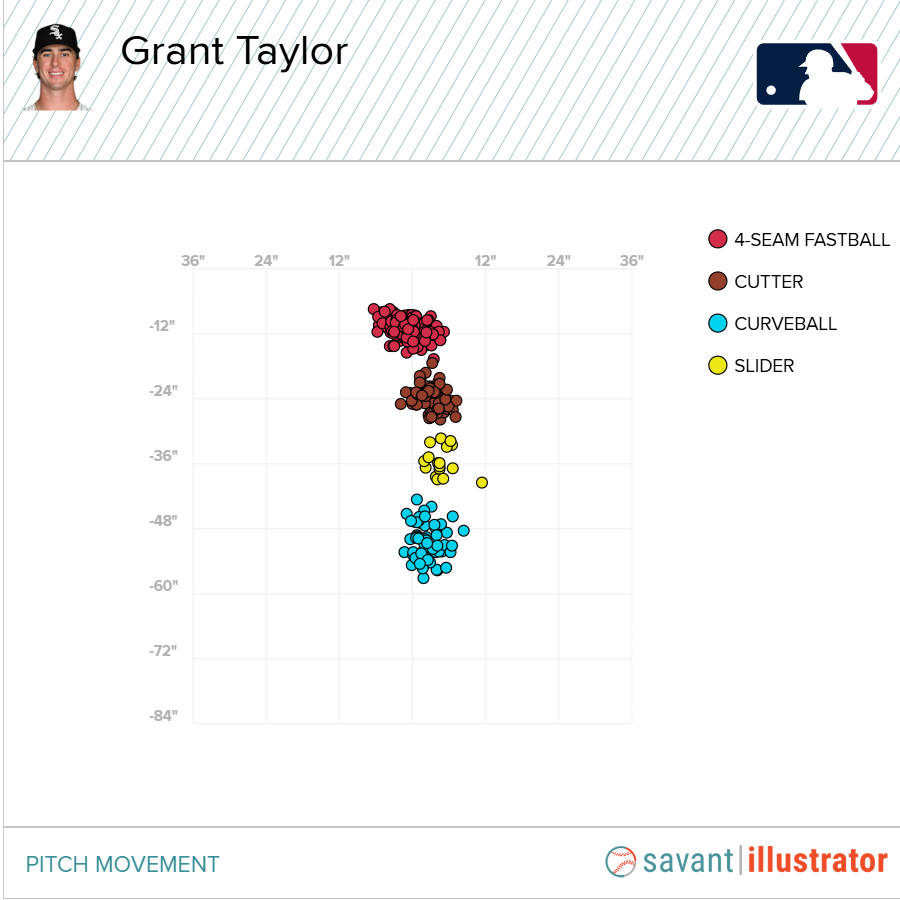

I think his struggles come down to his secondaries. Who are the three best closers in baseball currently? Tough question, but if you put me on the spot, I’d say some mix of Josh Hader, Mason Miller, Andrés Muñoz, and Edwin Diaz (depending on who the Sox played last). Taylor has much in common with these names: condensed arsenals, high K%, and minuscule FIPs. Furthermore, all of them have something distinct about their profiles that makes them hard to prepare for. Diaz has his arm slot; Hader has his wonky sinker shape; Miller has gas (and a weird slider to boot). Taylor, too, has a superpower: his cut-ride fastball from a high slot (56 degrees) is unhittable in the zone (30.8% in-zone whiff rate), and even when batters do make contact, the odd shape and insane velo make it a hard offering to really tag (.107 xwOBA). Taylor differs, however, in his ability to get whiffs, especially in zone, on his curveball and cutter.

Josh Hader’s most used secondary, his slider, is zoned 41% of the time and whiffed on in-zone 32% of the time. Mason Miller’s go-to secondary, also his slider, is zoned 40% of the time and is whiffed on in-zone 19% of the time. Taylor’s most used breaking pitch, his curve, is zoned 50% of the time and whiffed on in the zone 6% of the time. Put in other terms, when batters are swinging at a curveball in the zone against Taylor, they’re making contact about 94% of the time. For his cutter, utilized 22% of the time, the pitch has yielded passable results thus far (woBA of .284). However, without a real outlier shape and an xwOBA of .362, there are clear vulnerabilities in both of Taylor’s secondary offerings.

In explaining these weaknesses, I’ll point to a few potential foibles in Taylor’s approach. One is pitch usage patterns. When Taylor’s behind in the count, he almost entirely scraps his curveball – opting to throw his cutter and 4 seamer a roughly equivalent amount. More granular, Taylor throws his cutter around 70% of the time in 3-ball counts and 72% of the time in 2-0 counts. In no other count does he throw the pitch over 30% of the time. And although this predictability has yet to impact his top-line stats, there are worrying signals within his batted ball data. His cutter has surrendered the highest average exit velocity among any of his pitches (92.4 mph), and batters are running a 57% hard hit rate on the pitch. Having a “meh” cutter as your third offering is livable for a rookie reliever, but implementing usage patterns that expose it in the highest leverage moments is not ideal.

His curveball is a trickier matter. Certainly, its 6% in-zone whiff rate is poor, but its 46% in-zone swing rate speaks to the pitch’s bowel-locking effects. From a usage standpoint, I also think that he mixes it up well enough, using it off his four-seamer when up in the count about 21% of the time. Unlike his cutter, though, his inability to get whiffs in zone on the curveball is costing him – Taylor’s allowing a .294 batting average with the pitch. Common patterns emerge when analyzing who’s making contact and how they’re doing it. Of the 10 batted ball events coming off his curveball, nine were hit by lefties. All were in the zone, and only one was above the belt. All came in either even or pitcher counts. When he’s up in the count against lefties, Taylor all but scraps the cutter, only throwing high 4 seamers or low curveballs. I think that there’s something about Taylor’s high arm slot and rigidly north-south movement profile that takes a lot of guesswork out of the hands of hitters, especially lefties who are very used to seeing low curves from righties.

In terms of my proposed fixes, if I could be so bold, I’d want to start with Taylor becoming less predictable with his secondaries. Neither his curveball nor cutter pop on stuff alone (they run FanGraphs Stuff+ of 72 and 80, respectively), but he has the kind of overall arsenal command that can soften those rough edges. With those skills, I think he could find more creative ways to make these pitches work throughout counts and keep hitters guessing. Additionally, I think another offering is needed if he’s going to remain a competitive leverage arm. Already, according to Baseball Savant, he’s mixing in a slider, but where I think he could really find paydirt is by bringing back this supposed kick change that he shelved when he moved into the closer role in Birmingham. The White Sox have demonstrated an ability to develop this pitch among their spinny supinators like Davis Martin and Shane Smith – I think that looking at another pitch that plays low in the zone, especially against lefties, all while taking his arsenal off the center line, could be fruitful.

What Makes a Good Leverage Reliever?

At times, while writing this piece, I’ve thought, “Is it stupid to be trying to draw conclusions from 10 curveball batted ball events over 20 innings?” And I think there’s some truth to this being a foolish endeavor. The sample size is, in some ways, very small – and Taylor is certainly getting unlucky to an extent (see xERA and the like). Taylor could go the next 10 appearances without giving up a run, and it wouldn’t shock me because that four-seamer is just so good. But in some ways, this 22-inning sample size might be significant. Mason Miller’s highest IP count in his career is 65; Josh Hader’s is 75. Whether it feels like it or not, Taylor has around a third of a closer’s season-long workload under his belt. And even if the batted ball data suggests that Taylor isn’t giving up the type of damaging contact that a true-talent low-four’s ERA reliever does, the bottom line is that closers are tasked with being the most consistent guy on the 26-man roster.

Unlike starters, high-level leverage arms don’t have time to let their results match their peripherals. When Mason Miller gives up a home run, he cannot point to its subpar exit velocity or a gust of wind that carried the ball out. He can’t complain about luck or the skill of the opposing hitters. He cannot get unlucky because his bad beats usually mean that his team lost. The best leverage arms win on the slimmest of margins – even when the guy in the box knows what’s coming. The issue with Taylor is that the guy across from him certainly has a sense of Taylor’s tendencies, and the curve and the cutter currently aren’t enough to make him right in the biggest moments.

While writing this piece, I read James Fegan’s insightful profile of Taylor following his three-run blowup against the Dodgers in Sox Machine. A quote Fegan included from Brian Bannister that stuck with me was when the Sox pitching coordinator said that his favorite closers are “power lefties and cutter righties.” Now, keen-eyed readers will note that Taylor isn’t either of those things. If you’re a pessimist, maybe you read that quote as Bannister trying to force Taylor into a mold he’s not best suited for. However, until Taylor is throwing 70% cutters like Emmanuel Clase, I don’t read his quote like that.

Maybe, hoping against hope, Bannister is signaling that Taylor isn’t an ideal closer candidate at all. Maybe, when Spring Training 2026 comes around and this 6 ‘3 fireballer reports to Camelback Ranch with 5 pitches he can locate for strikes, you can find a way to get him a spot in the rotation.

Follow us @SoxOn35th for more throughout the season!

Featured Image: David Banks-Imagn Images

The post Grant Taylor is the White Sox High-Leverage Arm: Is that a Good Thing? appeared first on Sox On 35th.