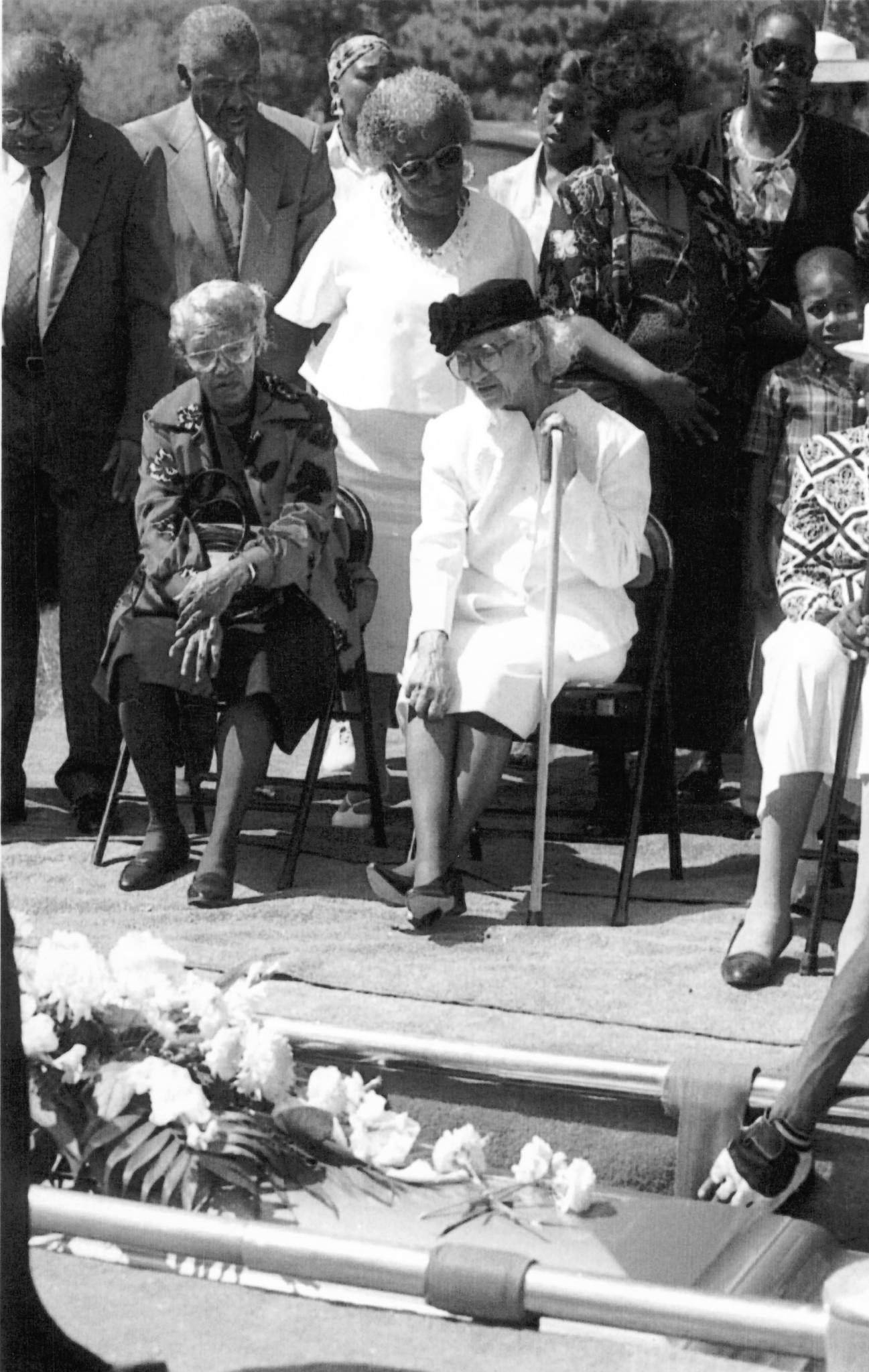

City officials, residents and researchers gathered at Columbus Park in the Austin neighborhood Tuesday night to remember the deadly heat wave 30 years ago — and to plan how to prevent future heat deaths.

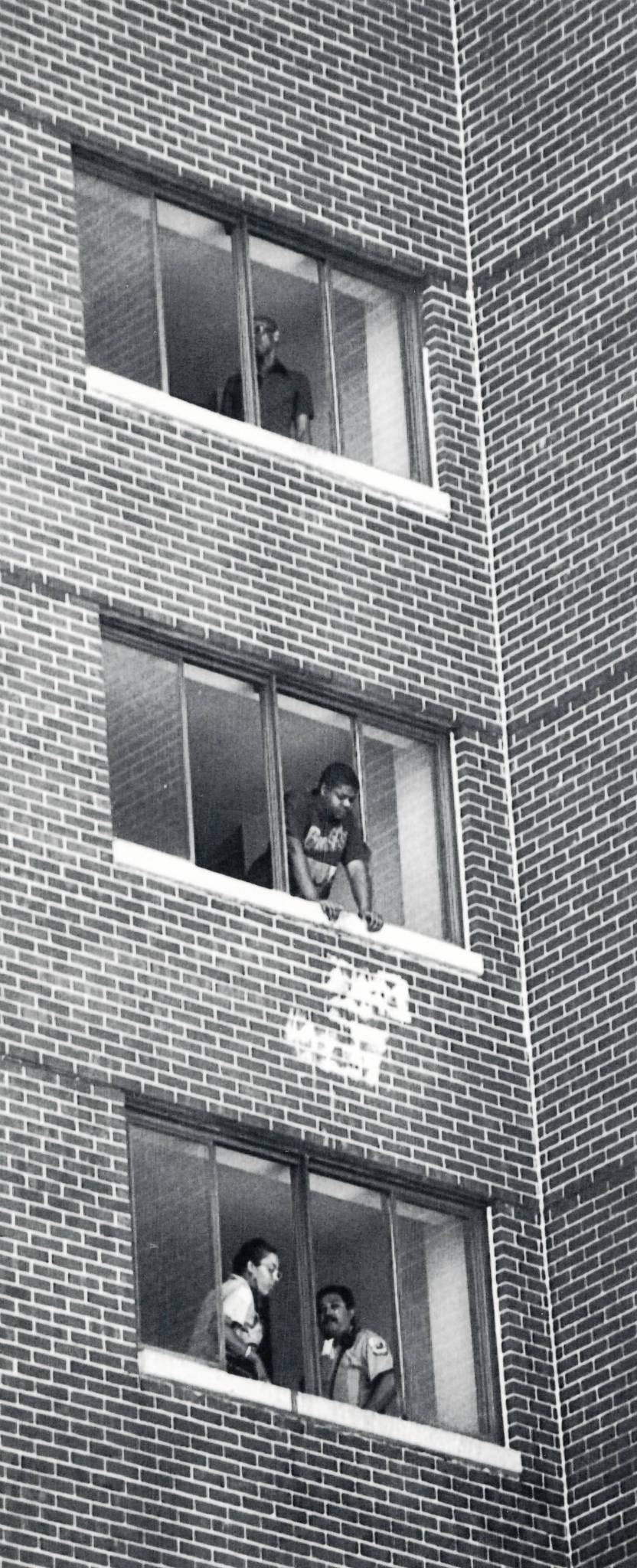

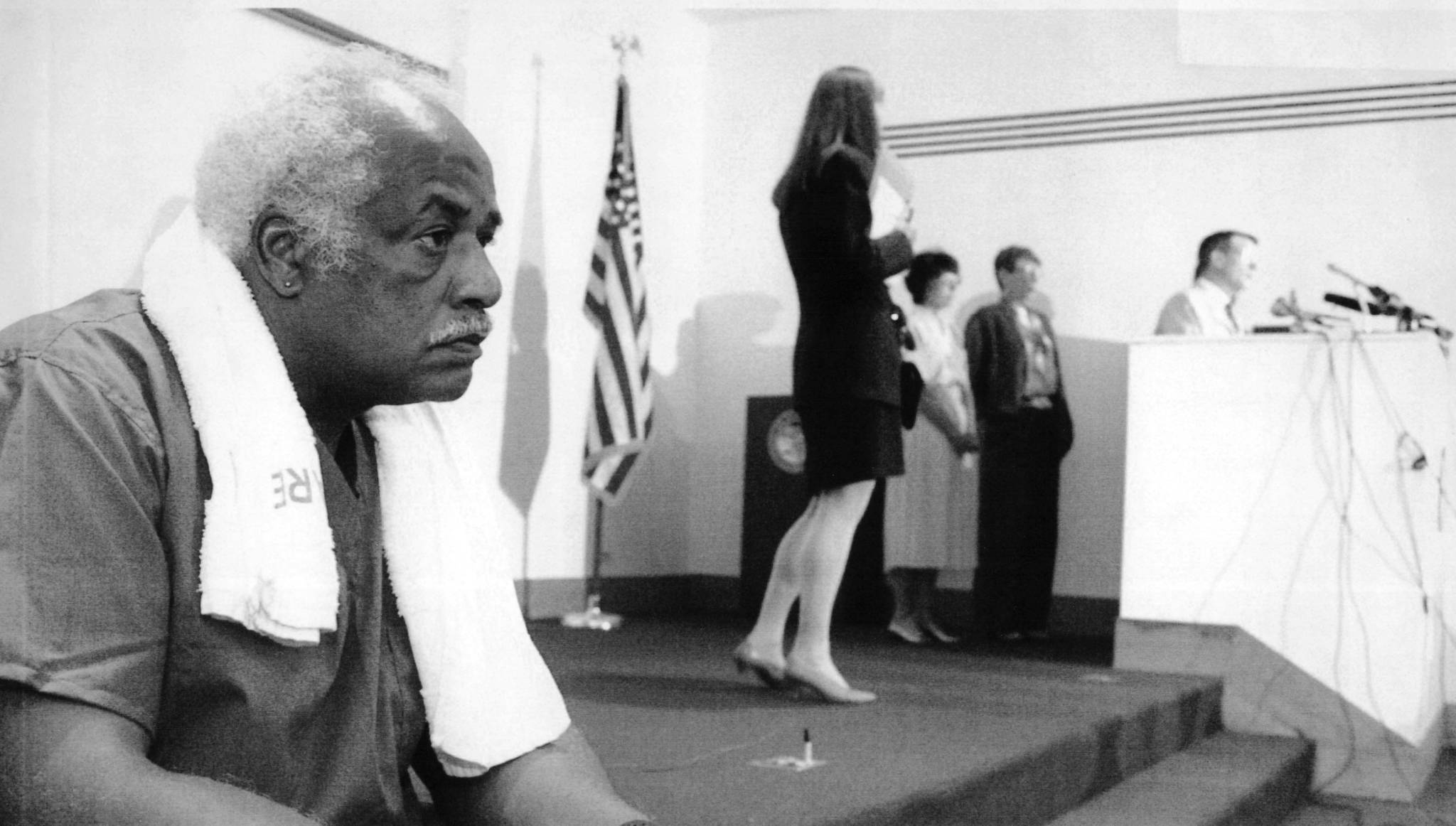

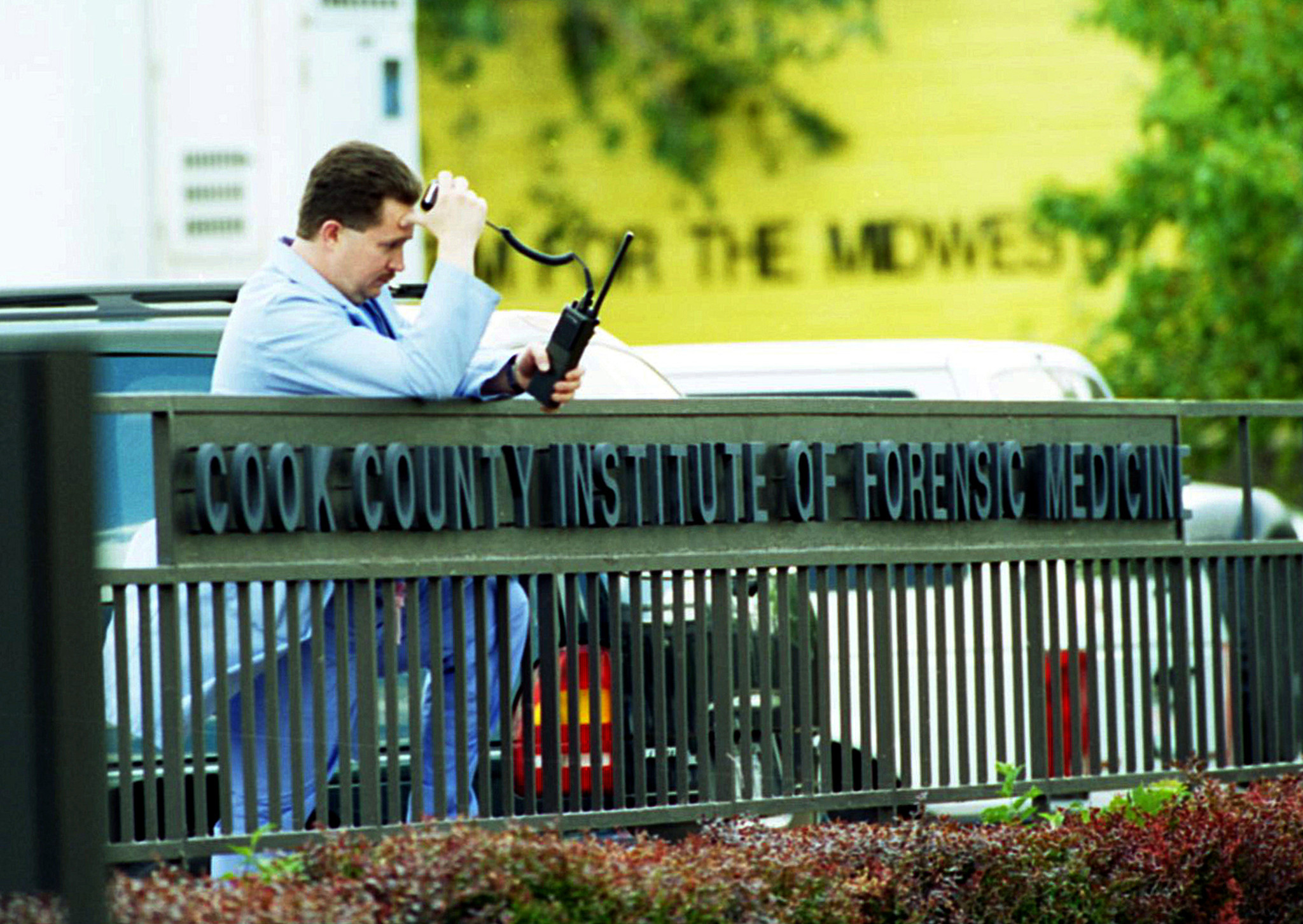

From July 12 to 15 in 1995, the heat index soared above 120 degrees, killing 739 people in the deadliest natural disaster in Illinois history. But the risk of death wasn’t the same for all residents — most of the victims lived in neighborhoods on the South and West sides, according to data from the Cook County medical examiner.

“During the 1995 heat wave, it became abundantly clear that environmental crises are never just about the weather,” said Mayor Brandon Johnson. “In fact, they are more about equity and access and justice.”

Today, residents of these neighborhoods — where historic redlining and unequal investment by city government have often occurred — are still statistically more likely to experience poverty, air pollution and deadly diseases like cancer. These factors can put people at greater risk of sickness or death during extreme heat waves, according to a team of researchers from Northwestern University who presented at the event.

The team, the Defusing Disasters Working Group, compiled data on citywide heat deaths to produce Chicago’s first heat vulnerability index. The tool shows which Chicago neighborhoods are at the highest risk during heat waves, based on not only their history of heat-related deaths but also on several other factors, including demographics, land use and air conditioning access.

This initial version of the map shows a band of neighborhoods stretching from Chatham and Englewood in the south to Austin and Portage Park farther north where heat vulnerability is the highest. Neighborhoods closer to Lake Michigan tended to have lower scores, while those farther inland often had higher scores.

The group is also surveying Chicagoans on what services they most want to see from the city during heat waves, which they’ll use to inform policy recommendations for future heat waves.

“As a disaster responder, I can take a look at that map and disaster response plan, and say, ‘Where might I want to focus my efforts? How does that help me identify my patients earlier?’” said Jennifer Chan, a Northwestern professor and team member.

So far, the top responses that residents have voted for include offering water at bus and train stops, providing more emergency shelters, and prioritizing parks and other green spaces.

The city has faced criticism in recent years for its emergency response plans during heat waves. Though Chicago’s Office of Emergency Management advertised that over 280 cooling centers were open during a recent heat wave in June, the Tribune found that almost half of those centers were sprinklers and spray features that were running at parks. Many cooling centers are stationed at city buildings that don’t remain open beyond their regular business hours, and none of them are open overnight.

During Tuesday’s event, as city officials shivered in the blasting air conditioning at the Columbus Park Refectory, residents nearby in Austin blew up inflatable pools and sold cold drinks on street corners to keep themselves cool as the heat index soared into the high 90s.

Rachel Williams, a Roseland resident who spoke on a panel about heat vulnerability after Johnson’s speech, said the city also needs to invest in cooling centers that aren’t just city-run buildings. Many people might feel safer seeking shelter at a place they’re familiar with, like churches or schools, than at police stations, she said.

“Most Black and Brown neighborhoods have a plethora of churches. Are they running consistently? Are (city officials) making sure that they have relationships?” Williams said. “In ’95, as a 4-year-old, I actually do remember going to some of those churches to stay cool during that time. And so that actually means investing in spaces that may seem unlikely.”

Human-made climate change is making summers in the Midwest more humid overall, even as seasonal high temperatures have rarely broken records in recent years. According to experts, sweltering summer nights, in particular, have become more common. In Chicago, while overall summer average temperatures have warmed by 1.7 degrees between 1970 and 2024, average overnight lows have increased by 2.5 degrees in that same period.

Johnson said his administration will consider policy recommendations from the Defusing Disasters group as the city plans for future heat waves.

“At a time when the federal government is dismantling not only environmental protections, but also federal disaster relief funding, this is the type of work that is needed,” Johnson said. “This project is a model of how community, academia and city government can work together to make sure no one in our city falls through the cracks and ensure that everyone is protected.”

Lily Carey is a freelancer.