Japanese pitchers sometimes need adjustment time when they come to MLB. The size of the baseball could have something to do with it.

Many pixels have been spilled regarding the adjustments Japanese pitchers must make transitioning to American baseball. Most attention focuses on the differences in the official baseballs used in the Japanese (NPB) and American (MLB) major professional leagues. The differences in physical dimensions between those baseballs has been of particular interest. This has become a focal point locally after the Cubs signed Shōta Imanaga, an elite moundsman coming off eight seasons of very good pitching in NPB.

What we attempt here is to examine the differences in dimensions using specimens readily available for purchase and inspection. We will not try to compare methods of manufacture, internal composition, or relative pregame treatments of the leather surfaces. That’s a much different subject.

An overview of the MLB baseball itself is in order. The physical dimensions of the ball have been one of the immutable aspects of the American game. They are covered in Rule 3.01: “It shall weigh not less than 5 nor more than 5¼ ounces, and measure not less than 9 nor more than 9¼ inches in circumference.” These were established by the National Association (1871-75) in 1872, and have since been adopted by all its professional successors. In its initial season, the Association had no standards, and decreed that the home team supply the game balls for all contests. When the inevitable abuses arose, the standards we now know were put in place.

All baseballs illustrated for this article are from the personal collection of the author.

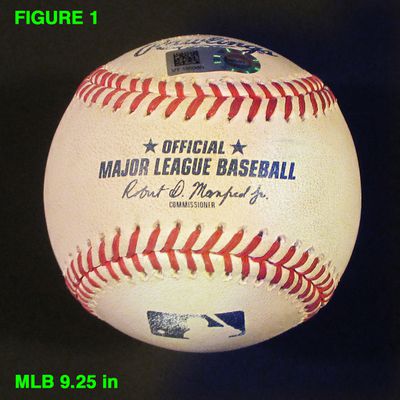

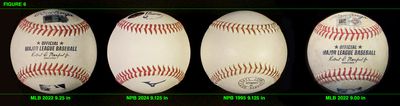

FIGURE 1: An official MLB ball, game used at Wrigley Field in 2022. Circumference 9¼ inches. This is the maximum limit under MLB rules.

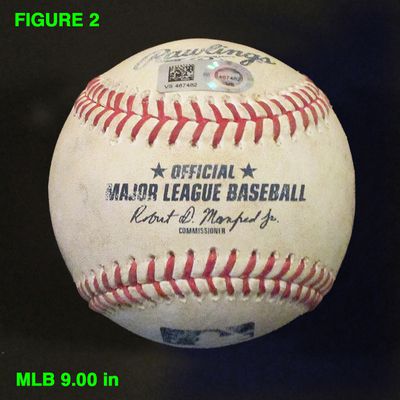

FIGURE 2: An official MLB ball, also game used at Wrigley in 2022. Circumference 9.00 inches, the minimum limit under the rules.

FIGURE 3: The two baseballs side-by-side, with guides for comparison. This is the difference in tolerance allowed under MLB rules. I have no doubt that a professional player can tell the difference, and how often do you see a pitcher ask an umpire for a different baseball, after having already received a fresh one?

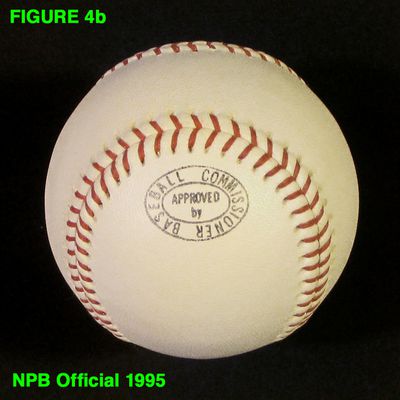

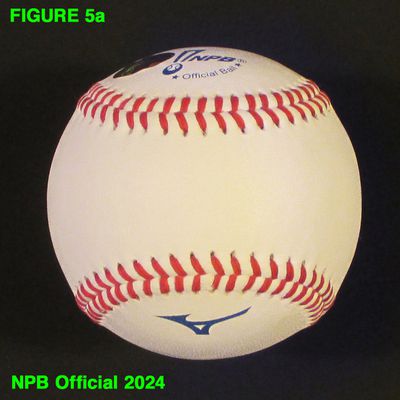

Unlike MLB, which has had a designated supplier of official balls from the beginning (the current supplier, Rawlings, has held the MLB contract since 1977), NPB did not use an official supplier until 2009. Before then, each team used baseballs made by multiple manufacturers, approved after inspection by the NPB office. These baseballs bore no imprint except the NPB handstamp of approval, the suppliers were essentially anonymous. As happened in the U.S. over a century before, questionable aspects of this practice forced NPB to adopt a more formal chain of supply. Mizuno has made official NPB baseballs from 2009.

FIGURE 4a/b: A pre-Mizuno approved NPB baseball, purchased in 1995 from the Yakult Swallows team shop. Circumference 9⅛ inches.

FIGURE 5a/b: Current Mizuno NPB official baseball, purchased from Mizuno in 2024. Circumference 9⅛ inches.

FIGURE 6: MLB and NPB official baseballs in a row, with guides for comparison. (Larger version of image here)

The NPB specimens, though made by different suppliers separated by nearly three decades, have remained remarkably similar. Some recent articles have stated circumferences for NPB baseballs as small as 8⅞ inches. If it can be taken that the NPB balls illustrated here represent the upper limits within their rules, they fall well within MLB tolerances. Even the minimum NPB standards would differ very little from MLB. It should be noted that baseballs used in the World Baseball Classic tournaments have all been manufactured by Rawlings, and have used MLB standards for size and weight. Japanese players have thus certainly been familiar with the use of the MLB baseball in elite contests.

One readily visible difference is in the seams, I’d go so far as to say that difference is more significant than the size difference. The NPB seams are definitely smaller, and thus make a wider distance at points where they are closest together (the so-called “sweet spots”). Both baseballs use 108 pairs of stitches. 108 pairs has been standard in MLB since 1919, previously the number was 116, and the earliest baseballs even more.

The conventional wisdom is that the smaller seams make for a better grip overall. A personal tactile inspection also confirms that the surface of the NPB baseballs is “tackier” than MLB, whose fresh-from-the-factory product has always been noted for slickness. Both leagues use pregame treatments intended to increase finger grip.

This ends the NPB/MLB visual comparisons. Have at it.

And now for something (sort of) completely different. As regular readers know, Al LOVES sleuthing. So here’s a sleuth using some older spheres.

1930 was a year of historic offense in MLB. The entire NL hit .303, Bill Terry became the last NL batter to hit .400, Hack Wilson set an NL record for home runs that stood until steroids, as well as an RBI record for MLB that may never be broken and only the Washington Senators posted a team ERA under 4.00. The Philadelphia Phillies posted a team batting average of .315 and a team ERA of 6.71. So what happened? As has been the case since time immemorial, the baseballs did it, or so they say.

Conspiracy theorists, (i.e. pitchers in 1930), maintained that it was not that the baseball was juiced, but that the seams were sunken, making it almost impossible to effectively throw the (relatively few) breaking pitches of the time. Let’s have a look.

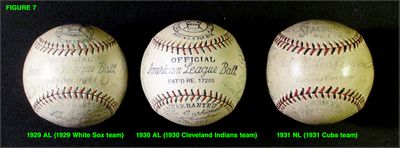

In order to do this, we must reliably date game balls to a specific year. Since imprints often do not vary for long stretches of time, how can this be done? By dating team-signed official balls. A baseball signed by a full team, or close, can be dated to a specific year through comparisons of the rosters.

The baseballs used for this illustration are team-signed baseballs dated to the years in question. They are photographed to display the official imprints, the signatures are, for the most part, not visible. It should be noted that AL and NL baseballs were made by the same company (Spalding), even though the Reach brand was used for the AL baseballs. Spalding had acquired Reach in 1889, but continued to use the Reach trademark for several decades.

FIGURE 7: L-R, 1929 AL, 1930 AL, 1931 NL. What jumps out immediately is that there was a reaction in 1931. The threads in the seams are heavier, the seams themselves larger. In fact, the size of the seams and heaviness of the threading is the same as current baseballs. Beginning in 1931, MLB baseballs have a modern appearance, except for the color of the threads.

It comes down to the difference between 1929 and 1930. The overall size of the seams and threading is the same, the difference, and it may be difficult to see in the photos, is that the grooves cut into the leather for the threading are deeper in the 1930 ball. The threads themselves do not rise above the leather surface. If there is a discernible difference, this is it.

Of course, one would prefer far more specimens providing a more representative sampling, but this will simply have to do.

One more.

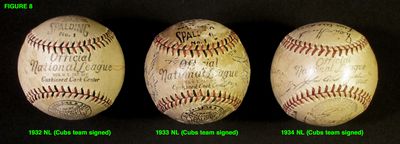

FIGURE 8: L-R, 1932 NL, 1933 NL, 1934 NL, all Cubs team-signed balls. This represents the transition to the modern look. Until 1934, the threading was blue and red for AL baseballs, black and red for NL baseballs. In 1934 both leagues went all red. Survivng correspondence between MLB and Spalding suggests this was an economy measure. Nothing is new under the sun.

Cost effective it might have been, but something got lost in the translation. Many thanks for all attention.